Since I started collecting items for this web page on euthanasia I have been struck by the blatant hypocrisy of some of the authors of articles and letters on the topic who, while delivering their opinions have, in most - if not in all - cases failed to inform readers of their religious affiliations, which in most cases informs their comments. This shows, yet again, that religion has no place in areas such as this.

Article in THE AUSTRALIAN:

The decision on whether and how to tell patients they have a terminal disease can have a telling effect on doctors.

KENNETH FREED reports from New York on this situationStillness shrouded the room, muffling even the bleep of the heart monitoring machine and the gurgle of the respirator. A human being was about to die.

A 26-year-old woman lay unmoving on the bed. The cancer on her brain already had snuffed out the awareness that separates the living from the dead. A doctor, with the patient’s mother holding firmly to his hand, reached for the resuscitator connection and pulled it.

For 10 almost unendurable minutes, the doctor and mother watched silently as the pulsating line on the monitor slowly evened and then went flat. The beep became a droning tone. A life was “terminated”.

In another hospital at another time, a different doctor sat in an examination room with a woman also dying of cancer. All the sophisticated means at his profession’s command - radiation therapy, surgery, drugs - could do nothing more than still some of the pain, temporarily.

The question came: “Is my illness terminal?”

The doctor was taken aback. He had not mentioned death directly but he had explained the statistics, had held nothing back, had raised no false hopes.

So he answered: “Yes, your condition is terminal.” With those words, he recalled, she “dissolved in front of me.”

Yet a different scene: A young woman with old-fashioned ideas of love and sexual behaviour listened as the doctor explained that the surgery and radiation used to treat her ovarian cancer had all but eliminated any chance for satisfactory physical love in the short time before her death.

“I’ve waited so long to start living and now I’m going to die,” she told the physician.

“Terminal,” “terminated,” mechanic’s words, impersonal expressions used by doctors in the same way outsiders talk about their own jobs.

But is it the same? How does a person whose career is dedicated to saving, healing and prevention deal with agony, disfiguration and death?

Several doctors and nurses who treat cancer patients exclusively were interviewed about the psychological and emotional stresses of their jobs and how they cope with those stresses, if they do.

Nearly everyone knows of doctors who seem to have built a wall, a callus of indifference against the suffering and despair of their patients: distant authority figures who condescendingly treat patients like so many defective machines.

For the most part, though, those interviewed for this story showed deep feelings for their patients and a constant awareness of the psychological needs of those under treatment.

To the doctor, a radiation therapist, who told his patient she was terminal, the episode taught him an indelible lesson.

“I could never do that again,” he said. “She was devastated. I’ve never used that word again….. There is a away to be realistic which is supportive, and there is a way to be realistic which is cold. I’ll never be cold again.”

The doctor who said this is a 41-year-old mid-western who trained as a radiation therapist in some of the best medical schools and institutions in this country and overseas and who has been treating cancer patients for 12 years. He requested anonymity and will be called Dr J.

Do you run into cases, even after all these years, that make you cry? He was asked. “Oh, yes,” he replied. “What I do is get up and wash my hands. I wash my hands a lot.”

Without ever mentioning it, Dr J. leaves an impression that, while he is friendly, he is not really a friend. “I can be a friendly doctor, but I think the patients need to have me in a white coat, and they never call me Jim,” he said.

The patients “need to have me for an authority figure, someone they can put their trust in, and you don’t do that with someone you sit down with and play bridge with and call Jim.”

“I think it is necessary for them to feel that the doctor is thinking about their problem rather than that Jim is thinking about their problem.”

It seems almost universal among doctors to touch patients in a friendly manner, but Dr J. talked about the need for touching with intensity. “I always touch them, always, always. That is very important.”

Another doctor interviewed did not mind being named. He is Michael Van Scoy-Mosher, a 36-year-old New Yorker who affects a hip style, mod clothes, neck chains, open shirts and a hair style best described as a curly bush.

But this apparent playboy has what all the others agree is the toughest practice of all. Van Scoy-Mosher is an oncologist – a tumor specialist. He gives chemotherapy and usually attends cancer victims when they are taken to the hospital to die.

He described his practice with three other oncologists.

“About a third of the practice dies within a given year. Something we don’t deal with is taking care of terminal people. We deal with taking care of patients with cancer, their families, getting the most out of whatever they can.”

This distinction is critical, Van Scoy-Mosher believes. He is not shepherding dying people on their way to the grave, but rather helping them live in the time they have.

“Cancer is another government within your body. It has its own laws and it runs the show,” he said.

“The patients become dependent – the family runs their lives, the doctor runs their lives, everybody runs their lives. We have to try to restore them to the controls.”

Just as Dr J. finally saw the stress build until it forced him away, Van Scoy-Mosher has reached his limit and he, too is pulling back.

He is pulling out of his practice to take a teaching position, although he will continue to treat a small number of patients.

The following book reviews were in the Sydney Morning Herald:

PETER Singer is right. Our values are in crisis, though I am not sure that I agree with the assertion of his subtitle. It may be more accurate to say that our traditional ethics, too, are involved in the "Copernican revolution" Singer writes so well about.

Whether or not, we are all in his debt for raising the issues of life and death. Large issues such as these are unfashionable. Yet they are inescapable. Death, after all, is the one certainty for everyone.

Not that Rethinking Life And Death reads like a traditional meditation on death. Seven of the nine chapters are more in the journalistic mode. This distinction is meant as praise, not blame.

"To generalise is to be an idiot," Blake said, and Singer grounds his ethical explorations in a discussion of a number of well-known cases which dramatise issues such as death and its definition, the right to die, the question of abortion, the meaning of "human", the Karen Quinlan case and that of Tony Bland (one of the victims of the Hillsborough disaster, who was reduced to a vegetative state), and many others. The questions these cases raise, Singer says, "are the surface tremors resulting from major shifts deep in the bedrock of Western ethics"

He exposes the muddle, the inconsistency and sometimes the hypocrisy that surrounds these issues, though, in my view, sometimes in his eagerness to snatch the opportunity he rightly finds in technology, scientific knowledge and the availability of knowledge on the one hand and the decline of respect for traditional values on the other, he tends to throw the baby out with the bath water. Questions of value are, after all essentially the product of tradition. It is one thing to question traditional interpretations of ethical questions, but another to declare that these interpretations are "propped up by transparent fictions no-one can really believe".

This is an important book, however, because it attempts to remove the discussion of matters such as abortion, the right to die, the definition of death, quality of life versus the sanctity of lif,. the meaning of "humanity" and so on from the merely superficial and sensational. It sets them in a larger context of the "Copernican revolution" of meaning and value in which we find ourselves. But, in my view, Singer tends to ignore the other and perhaps deeper question which underlies the question of value: how we talk about it?

"A proposition is a queer thing," as Wittgenstein remarked, and the proposition - the world-view - underlying Rethinking Life & Death seems to be based on the old Enlightenment model, which is that reason can ultimately sort things out and describe what is the case. So, for instance, the crux of the argument against specieism, the notion that human beings are somehow superior to animals, seems to be that "the way in which we divide beings into species does not reflect a natural order of things or a reality out there in the world".

In a comparison with Nuland's How We Die, the point I am making becomes clearer. Nuland, a doctor rather than a philosopher, is more interested in the microcosm than with the macrocosm; in the illness — specific human and physical demand of suffering and death — rather than in the larger issues Singer explores. His observation is shrewd and to the point: "Decisions about continuation of treatment are influenced by the enthusiasm of doctors who propose them", for instance. But his approach is poetic and intuitive rather than merely rational. For him. what matters is the art of dying, which is the other side of the art of living: "The dignity that we seek in dying must be found in the dignity with which we have lived our lives."

Singer would not deny this, of course. Indeed, his rewriting of the commandments with which his book concludes implicitly endorses it Similarly, his objections to the arrogance which defines human superiority as an absolute right to use and even exploit the rest of creation, the questions he poses to both the pro-choice and right to hfe camps in the abortion debate, his sense of the responsibilities of medical people to community in the widest sense and his respect for life in as variety and range, all reflect the limits of the merely rational; the sense of mystery Nuland presupposes for all his professed scepticism.

When Nuland writes that "death belongs to the dying and to those who love them" he is touching on this mystery. Singer often moves towards it also, of course. But his premises — solidly secular, unwilling to accept a level of reality beyond what is observable and rational or to acknowledge a meaning and purpose which exceeds our human calculation - do not allow him to explore It. Yet, in the long run, the evidence in both books suggests that Hamlet was right, that there are more things in heaven and on earth than are dreamed of by rational philosophies.

la effect, it seems to me that Singer has written a book about issues which are essentially religious, but lacks the language to eiplore them properly. The language of symbol and metaphor is able to do this and also has its own logic, its own laws, its own test of verifiability and falsification. But the remark that, after Darwin, "no intelligent and unbiased student of evidence could any longer believe in the literal truth of Genesis" suggests that Singer does not really understand this. Genesis is myth, not science. The heart of all religions, Christianity included, is belief in realities at present unseen and beyond rational calculations, realities which will be apprehended differently al different times and in different cultures. So there is built into all religious traditions a principle of adaptation and change. The fact that, in our society, many people who call themselves religious do not seem to be aware of this calls into question the nature of their belief, not belief in itself.

Singer has the ability to deal with large and urgent cootemporary issues. It would be interesting to see whether his next book will tackle this question of religion, how we talk about and define value, and how we rediscover and revive the grand narratives which are not dead but have only gone underground.

Veronica Brady is Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Western Australia.

The euthanasia issue won’t just disappear because Philip Ruddock wants it to and because he bans Nitschke’s book and overturns the Northern Territory’s Euthanasia Act.

This article from The Age on 4 July 2006 (what a good date to report on a struggle for independence!!) puts the next fight firmly in Ruddock’s hands!

The Commonwealth is heading for a showdown with South Australia over plans to introduce a voluntary euthanasia bill before the end of the year.

A decade ago, the Federal Government overturned Northern Territory legislation allowing euthanasia. But Canberra does not have the same power over states as it does over territories, which means that if a bill goes through it will stand.

After reports that an Adelaide woman had traveled to Switzerland to end her life, two members of the SA Parliament have signalled their intention to put up a voluntary euthanasia bill.

Labor backbencher Steph Key said that while it would be the sixth time such a bill had been introduced in SA in the past decade or so, she was hopeful that this time it would pass. Ms Key, who has just returned from a fact-finding mission to the Netherlands, and independent MP Bob Such said they planned to introduce a euthanasia bill.

“I get the impression there is genuine support for voluntary euthanasia,” Ms Key said.

In 1997, a year after the Howard government arrived as a blot on the landscape, Kevin Andrews, a member of Howard's government and a member of the religious right, was instrumental in getting the Northern Territory's euthanasia legislation overturned. "We will show you who is the boss around here and you will accept our moral precepts on everything we do". And all their moral precepts became hallmarks of one of Australia's most immoral governments, which is some achievement!

Now we have a Rudd government, and it looks as if we are in for more of the same.

However, a glimmer of hope has appeared on the euthanasia horizon because the conservative ALP state government in Victoria is putting forward a "Physician Assisted Dying" Bill in 2008.

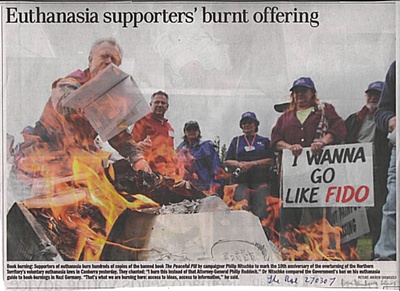

The following picture was in The Age newspaper on 27 March 2007:

The caption reads: BOOK BURNING: Supporters of euthanasia burn hundreds of copies of the banned book The Peaceful Pill by campaigner Philip Nitschke to mark the 10th anniversary of the overturning of the Northern Territory's voluntary euthanasia laws in Canberra yesterday (26 March 2007). They chanted: "I burn this instead of that Attorney-General Philip Ruddock." Dr Nitschke compared the Government's ban on his euthanasia guide to book-burning in Nazi Germany. "That's what we are burning here: access to ideas, access to information," he said.

This article appeared in TheAge newpaper on 10 March 2008, opening once more the debate about legalising euthanasia. A friend of ours is believed to have recently chosen this form of death, illegal though it is in Australia, rather than go through the torments of the disease from which he was going to die a cruel and unavoidable and dragged out death and inflict untold suffering on himself, his beloved partner and those around him.

TOMORROW, a group of senior citizens will gather in Lower Templestowe. Their mission: to train in the rites of a peaceful death by asphyxiation, carbon monoxide poisoning and the powerful barbiturate Nembutal — the drug that 78-year-old mesothelioma sufferer Don Flounders was caught importing last month.

Their education will be overseen by Exit International, the organisation headed by Dr Philip Nitschke that maintains a precarious dance with the law while ensuring its predominantly elderly or terminally ill members receive instruction on how to induce a relatively quick and peaceful death.

The workshop comes at a time of growing debate about voluntary euthanasia: Greens senator Bob Brown is pushing to have the Northern Territory's former right-to-die laws restored (they were overridden by the Howard government) and has called on Prime Minister Kevin Rudd to allow a conscience vote on the issue.

Ironically, most of our staunchest advocates for assisted suicide and the reinstatement of the Northern Territory's short-lived laws do not have a voice in the argument — because they are dying. Unable to dedicate their precious remaining time to influencing politicians, they wait for a potentially gruesome end, denied ultimate medical assistance that residents of progressive European nations take for granted.

Many other advocates of voluntary euthanasia have already been lost. One was my father, Alan Coleman. A true son of St Kilda, he was typically blue-collar — honest, hard-working and a dedicated family man. He tinkered with cars, grew tomatoes and watched war movies. A boilermaker, he worked his guts out his whole life. He didn't deserve the death he was dealt.

After his cancer diagnosis, but before his health declined, we discussed the plight of Maria Korp, who was at the time alive but declared brain dead. Dad grunted his assent at the decision to allow her to die, but was sickened that she would be left to starve to death. His voice was gruff: "If that ever happens to us," he nodded towards Mum, not liking to make a specific allusion to his terminal illness, "flick the switch. Don't think about it, just do it."

In the end there was only a morphine drip and, in the ultimate kick in the teeth, he died the same death as Maria Korp, only Alan kept regaining consciousness, enduring each of the four tumours eating away at his body as he slowly starved and dehydrated to death, all the while paralysed from the neck down and unable to speak.

Theoretically, I knew how to boost the morphine dose, but I didn't know how much it would take to kill him. I was afraid of increasing his suffering without bringing an end to his misery, and I also knew hospital staff were monitoring the machine-fed doses with a thoroughness that would have revealed family interference. I regret my cowardice every day.

The tumour that ate his bowel caused him unendurable pain, while those that rent his lungs caused him to fight for every shallow breath. But it was the spinal tumour that finished him mentally and physically. Not only did it paralyse him, in a fierce and cruel twist, it seemed to magnify his sense of pain, so that between bouts of unconsciousness he had torturous waking moments in which he experienced the shut-down of his organs over seven days, each small death defeating the massive morphine doses with outrageous breakthroughs of pain.

The effect of a dehydrated human body is something to behold. At first there were consistent attempts to keep his mouth wet, but the longer he survived the more difficult it became, until the skin of his mouth dried to the consistency of desiccated coconut. Over a few days the dryness spread throughout his mouth and descended down his throat into the reaches of his oesophagus and windpipe. In his waking moments every breath he took was like a thousand paper cuts across that dead, flaked skin.

The once tall, handsome man had been whittled away to 35 kilograms and his mouth hung open in a pre-death rigor mortis, his body rigidly knotted with tension in his waking moments. He was just 58.

A workmate shook her head sadly at my description of his demise. "You wouldn't do it to a dog," she said, her voice thick with disgust.

She was right. My father is dead, but with hope his voice can still be heard in the debate on allowing the terminally ill the right to a peaceful death.

Michelle Coleman is a Melbourne freelance journalist.

Article in The Age:

By Julia Medew

THE meeting began like any other senior citizens' gathering on a sunny weekday afternoon. There was tea and coffee being poured under portraits of the Queen, but this time it was being served with images of lethal drug kits and instructions on suffocation bags.

More than 100 elderly people packed into the Templestowe Senior Citizens Centre after lunch yesterday to learn about peaceful, reliable and cost-effective ways to take their own lives.

The mostly healthy grey-haired bunch chatted passionately inside the bright hall about why they wanted to choose death over suffering if the time ever arrived.

After sitting through a free introductory lecture from euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke about his history and issues surrounding suicide, almost every attendee paid a $50 fee to stay on for a workshop on methods recommended by his organisation Exit International.

The attendees were asked to sign a disclaimer that declared they would not use the information "to advise, counsel or assist in the act of suicide".

"It's effectively saying that you won't take notice of what I'm saying," Dr Nitschke said.

He began the meeting by explaining that it was a crime to advise, counsel or assist someone to commit suicide in Australia — an offence that carries a maximum jail term of 14 years in Victoria and 20 years in other states.

He explained that although he had helped many terminally ill people achieve peaceful deaths using legal methods overseas, he understood some people who were not dying might want to take their own lives.

Dr Nitschke detailed the example of a couple who did not want to endure the loss of each other. They took their lives peacefully and had their ashes blended, he said.

A short time later he moved on to exactly what people paid to hear: "DIY Strategies".

In his first example, Dr Nitschke used still images of a woman named Betty, who was sitting in the crowd. He said he could not show the video of the procedure, but could point those interested to a website, as some seniors reached for their pens and pads.

Betty's strangely humorous prerecorded explanation of how to make your own suffocation device, which will kill you in 20 minutes for about $25, was then played.

"You can see why we all love Betty," Dr Nitschke joked as he pointed her out in the crowd.

He then spoke about the "single-shot coffee pot", a method for cooking lethal drugs using materials easily purchased in most states. Again he showed still images of a film available on the internet.

In June 2008 a bill was introduced to the Victorian State Parliament concerning euthanasia. The Bill is called "The Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008. The Parliament has been allowed a conscience vote on the issue so that it can be debated across party lines. Already, as was to be expected, the religious groups have come out against the proposal, and some have taken out a large newspaper advertisement, asking people to oppose the bill. Letters have for some time been appearing in the newspapers, and the debate has also been aired on national television.

In posting letters and articles debating the issues concerning the proposed Bill, I would be interested to know how the religious connections of many of the writers influence their approaches to euthanasia. It is important for people to advise where they are coming from in a debate of this sort

A duty of care

WE ACKNOWLEDGE and support the compassion underlying the article "Encounter with Rodney Syme", (Insight, 25-26/4). As practising palliative care physicians we also do our utmost to manage suffering. However, our intent is always to relieve suffering, never to take life away.

The patients we care for have life-limiting illnesses that often involve physical and emotional suffering. In this emotionally charged environment, our role is to enhance their quality of life and to apply the most up-to-date methods of palliative care and medicine with the aim of relieving pain and suffering at the end of life. In our experience, the overwhelming majority of patients can be made significantly more comfortable and symptoms need never be left untreated.

Currently it is ethically and legally permissible for doctors to administer appropriate medication in response to suffering in doses commensurate with the degree of suffering. It is not acceptable for the patient's death to be the primary goal.

We believe the correct response from a civilised society that aims to provide its citizens with the best possible standard of care is a greater investment in palliative care and palliative medicine. We oppose any legislation supporting physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.

We must have the choices we need

DOCTORS Jenny Hynson and Adrian Dabscheck (Letters, 3/5) oppose any legislation supporting voluntary euthanasia. They are free to do this. They are free not to use voluntary euthanasia themselves. I am a practising GP, and I would like to be free to use voluntary euthanasia for my patients, and for myself, if the situation arises.

I agree that the overwhelming majority of patients can be made more comfortable, but that is not everyone. There will remain a small percentage who cannot be made more comfortable, and it is cruel to force someone in this situation to exist in discomfort until their end finally comes.

Palliative care is good, but it is not perfect and there will always be some for whom it is not the answer, and who would choose to leave this life a little early. They should be allowed the choice to do so.

Meeting the needs of all

IT MAY be in the interests of Dr Hynson and Dr Dabscheck to prevent everyone from escaping inadequate palliative care, but it certainly isn't in the interests of all patients. The fact is, as they acknowledge, such care cannot satisfy the needs or wants of everybody.

Many people make their wishes known by advanced directives, or appoint a trusted person with an enduring power of medical attorney to make decisions for them if they become unable competently to do so. Thus, decisions regarding death can be made before one is in "an emotionally charged environment".

A patient already has the right to refuse medical treatment.

Neither Dr Rodney Syme nor anyone else that I'm aware of is trying to force people to opt for euthanasia (or have it foisted upon them). The choice should be our own. It should not be denied by doctors whose values and beliefs we do not share.

The acid test of care

THE palliative care physicians who oppose legislation permitting voluntary euthanasia acknowledge that the overwhelming majority of patients can benefit from palliative care. However, they are silent on the most difficult cases - the small minority who cannot be adequately treated this way.

It is this minority that really represents the acid test for the palliative care physicians' claimed intent "always to relieve suffering" - by adding the rider "never to take life away" they are left in limbo regarding this minority group, hence the silence.

Their reference to it being unacceptable for death to be the primary goal is presumably intended to infer that this would be the primary goal of any death-with-dignity legislation, again missing the point, since the primary goal is the elimination of unnecessary (and often unbearable) suffering, which palliative care is not always able to alleviate.

While physicians are entitled to their opinion on proposed death-with-dignity legislation, the days when they knew what was best for the rest of us should be a thing of the past. This issue concerns the right to a choice, not a matter of compulsion for those who don't want it, unlike the "we know what's best for everyone" attitude struck in their letter.

It's about quality of life

IT IS good that Dr Hynson and Dr Dabscheck "acknowledge and support the compassion" expressed in the article on Dr Rodney Syme. But the point is that end-of-life decisions should not merely be in the hand of the attendant physicians.

I look to a physician to provide medical care, not stand as a moral guardian. Surely the best palliative care need not be mutually exclusive to leaving the all important quality-of-life decision to the patient.

Allow me some rights too

DR HYNSON and Dr Dabscheck, you miss the point. It is not about you making the decision as to what I want done regarding the ending of my life. I want the right, in law, to make that decision for myself. It should be my right to choose between relief of suffering or ending my life. Not yours.

While I respect your compassionate position, I would ask you to respect my choice.

Greens MLC Colleen Hartland is happy to wait another two weeks for the second reading of her Physician Assisted Dying bill. "The longer we wait, the more support we get", said Colleen Hartland.

"Support has grown to an overwhelming 80% of Australians calling for the right to obtain assistance to die, should they need it. The bill has been available for over a month. I'm ready, and Victorians are ready. Let's get on with it."

"The bill provides compassion and support for people who are suffering intolerably, and who want to die. But it also provides safeguards, and regulates a process that is currently going on in the dark," said Colleen Hartland, MLC for Western Metropolitan Region.

"I would like doctors such as Dr Rodney Syme, who I admire for having the courage to act and speak out, to be able to assist in the open. They operate without support, but also without regulation. This legislation will bring it out into the light."

Ms Hartland outlined a range of safeguards in the bill, for patients, medical staff and other Victorians

"The process is transparent, yet private. There are independent checks at every stage, from the second opinion of a doctor, right through to a Coroner's report being presented to parliament. These safeguards are far superior to those in the present system."

"Individual doctors, organisations and health care providers may refuse to participate. At least two independent doctors must be satisfied that the patient is terminally ill or has an advance incurable illness, with no realistic prospect of recovery, and is suffering intolerably. Assistance can only be granted if palliative care is not suitable to the patient. There are penalties of 14 years prison for attempting to unduly influence a sufferer to make a request for physician assisted dying."

"Most importantly, anybody who assists the patient in a formal way, waives any right to inherit or benefit from the death, directly or indirectly. By removing completely the temptation of money or inheritance, we are removing completely any possibility that physician assisted dying will assist criminals. We are also removing any hint of stain upon the character of the people who assist those who request assistance to die."

"It is likely that the mere existence of physician assisted dying, may give people the courage to continue with the final stage of their illness. They would know that relief will be available, should they need it," said Ms Hartland.

Letter writers do not speak for me

THE open letter signed by the leaders of various churches in Saturday's Age stated their resistance to the Physician Assisted Dying Bill, currently with the State Government. No one can take this seriously. Opinion polls have consistently recorded rising numbers of people who realise that help in dying is to be welcomed: 82% at the latest poll. Therefore, these churches and recent statements by Archbishop Pell are representative of only 18% of the population.

They certainly do not represent me, nor any of my friends and acquaintances, with whom I have discussed this problem over many years.

Physician-assisted dying is for those who have chosen in advance not to continue living if their medical condition has become intolerable.

Safeguards are in place to ensure that it is the patient's choice, clearly expressed when of sound mind.

Those who wish to endure painful death are at liberty to do so. Those of us who do not so wish seek the legalisation of medical practice to provide the means to help us die. It is the choice that we seek and we resent the interference of strangers to compromise our wish for a good death.

Pauline Reilly, Aireys Inlet

The open letter stated that "the fear of being a burden is a major risk to the survival of those who are chronically ill."

Palliative Care Australia's own publication The Hardest Thing We Have Ever Done states that "carers experience an increase in adverse health effects related to stress, a change in eating patterns leading to weight loss, and a disruption of sleeping patterns leading to carer fatigue.

"Carers have reduced opportunity for social and physical activities, further reducing their own physical wellbeing … Carers report feelings such as guilt, fear, frustration, anger, resentment, anxiety, depression, loss of control and a sense of inadequacy."

The sense of burden is not just a "fear", it may be a devastating reality. To want to spare one's relatives and friends such distress may well represent a selfless act of altruism of the highest order — a thoroughly Christ-like act.

People have nothing to fear from this legislation, which demands careful medical practice for its implementation. More importantly, the person making the request for assistance in dying retains control over the process, as they must ingest the medication — no doctor may give them an injection that they do not want.

I want the right to choose

None of what I read in this expensive ad is valid or proves any reason to reject the bill. Words such as "may fail", "may lead", "usually arises", do not prove that they will. The statement that "the bill would not benefit Victorians who suffer from chronic illnesses, instead it would make protection of their lives dependent on the strength of their will to continue" is not based on fact.

How could they know this for sure? How dare they assume that I would not be able to make my own informed decision. This statement has no proven truth to it; it is just highlighted to frighten.

The member's bill 2008 is in the interests of all Victorians and we should have the right to choose, the right to decide how we live and how we die.

I understand that people disagree — I respect their decision. They have a choice — at present I do not. I am asking that they respect my right to choose.

Chance I’m happy to miss

I can agree that if I somewhat casually decide, during the course of my final illness, to have myself topped, and that if I am abetted in this decision by obliging assistants, uncaring medical staff and eager legatees, then my final illness will be cut short. I can also agree that I might, in consequence, miss out on a priceless opportunity to experience the ennobling effects of pain and suffering and to share that experience with my family and friends. I am, however, willing to take that chance.

Second, I would be interested to see evidence, over and above assertion and expressions of pious anxiety, that there would be "a moral pressure to relinquish one's hold on life". Third, I would suggest that there is something a little coy about the references to "similar legislation" being found wanting.

THE bill to legalise physician-assisted dying, more commonly and appropriately called physician-assisted suicide, has far-reaching implications.

For individuals, there comes the "duty to die" - the pressure to ask for death, even when they want to keep on living - to relieve distress on relatives or carers. This can also reflect a "societal" obligation, with pressure felt by someone in an overcrowded, understaffed nursing home, where there is an expectation that they will agree to die because it is better for society. Legalisation lends "state" approval for physician-assisted suicide as a valid option for people - including the young - to consider what they would otherwise not consider.

Patients may conclude that doctors would be less enthusiastic in their care if they think the patient should be prepared to die, and are supported in this view by society and the law. The option of good palliative care means that relief from pain and distress is increasingly achievable and obtainable. It is well known that many who wish to die change their minds when they receive good palliative care.

Killing should never be seen as a solution for misery.

DR LACHLAN Dunjey's letter (18/6) typifies the woolly logic of those who oppose dignified deaths for the terminally ill. First, the alleged "duty to die" pressure would come too late; the decision to opt for an assisted exit would have been made long before the patient reached this (real or imagined) state of vulnerability.

Second, he complains because people "including the young" might have their options broadened. In countries with voluntary euthanasia there is no proof that this has promoted suicide among the young. Third, his contention that doctors would be "less enthusiastic in their care" fails to take into account that the decision by the patient is made when he or she is still of sound mind. And where is the proof that "society and the law" support his views? Eighty-odd per cent of them clearly don't, at the last count.

Finally, the assertion that "good palliative care means that relief from pain and distress is increasingly achievable and obtainable" can only come from someone who hasn't watched too many people dying in agony recently.

Dr Dunjey, it's my life. If your religion or your moral code prevents you from providing the care your patient clearly requests, please leave the Nembutal on the fridge and get out of the way.

THE Physician Assisted Dying Bill calls for the legislated right to voluntary euthanasia. Whether or not euthanasia is necessary or preferable may be debatable, but it cannot be described as democratic and pro-choice. Death irrevocably removes all freedom to choose.

Euthanasia encourages the dying to give up the freedom to choose any more. A democratic society should oppose any legislation that removes freedom and choice from a weaker minority by the majority. The only freedom that should not be legislated is the freedom to give up all freedom.

Dr Graeme Duke, director, Critical Care Department, The Northern Hospital, Epping

I AM very concerned about the Physician Assisted Dying bill. I am severely disabled and use a wheelchair full-time. I also have very severe spinal pain on a daily basis, which isn't well controlled even with morphine.

About 20 years ago I decided I wanted to die and doctors then believed I did not have much longer to live. I attempted suicide several times and my wish to die lasted more than 10 years. If this bill had been in place when I wanted to die, I would have qualified for "assisted dying" and I would have requested it. Then no one would ever have known that the doctors were wrong in thinking I didn't have long to live and I would have missed the best years of my life.

This bill is a very real threat to all who now feel as desperate as I once did. Far from achieving "dignity" only in death, what suffering people like me really want and need is support and encouragement to live with dignity, until we die naturally.

BASED on the available evidence and our experience in specialist palliative care we believe that energy and resources should be directed not towards legalising physician-assisted killing but to enhancing the quality of palliative care provision. People diagnosed with a terminal illness commonly desire symptom relief and open communication with health providers who are comfortable in discussing issues of death and dying. However, the training in end-of-life care available to health professionals is limited.

Despite some excellent initiatives in palliative care in Australia, there remain significant shortfalls in resources available to support patients and their families. Hence, it seems illogical to enter into resource-intensive activities aimed at legalising assisted killing when our capacity to provide quality end-of-life care is often inadequate.

In our collective clinical experience spanning more than 25 years, requests for euthanasia remain extremely rare. Our society would not tolerate inadequate prenatal and postnatal health care nor should it accept suboptimal end-of-life care.

IT IS no wonder the debate on the Physician Assisted Dying bill in Victoria has been delayed. The conviction for manslaughter of two women in NSW shows how dangerous legalised mercy killing would be. Family members struggling to care for their sick and lured by inheritance would find legalised killing a convenient way out. Swallowing a drug designed to kill pets after your partner changed your will is no dignified death!

Luke McCormack, HadfieldWHILE I have every sympathy with Alison Davis' situation (Letters, 20/6), the exception does not make the rule. When palliative care doctors have removed a patient's source of nutrition then they are admitting that that patient is about to die. If the same patient's agony is only controlled (intermittently) by massive quantities of morphine, which in turn keeps them largely comatose, where is the logic in prolonging "life" if that patient had already expressed, while still of sound mind, the firm wish that their life be terminated under such circumstances?

Lewis Winders, Sheffield, Tasmania

Focus on easing pain

Central to the debate on euthanasia is the provision of quality palliative care. ON THE surface, the physician-assisted suicide legislation now before the State Parliament has the appearance of being humane and well-intentioned.

We all fear a "bad" death — one involving intolerable levels of pain and physical suffering, often accompanied by loss of autonomy and the perceived indignity of total dependence on others. What humane society would deny people in such dire end-of-life situations legal recourse to the help of a physician to end life prematurely?

But, as a palliative care doctor, I find that I have several problems with this proposed legislation, and with some of the assumptions behind it.

First, it seems to me, it reflects a disturbing degradation of the value we, as a society, place on human life. I don't know whether it is symptomatic of the fact that we have lost perspective, following a century of mass genocides and the growing prospect of further catastrophic loss of human life as a result of climate change. Or, perhaps, in our consumer-driven society, human life itself has become just another expendable commodity in a throwaway world.

Whatever the case, the primacy of human life appears to have been slowly whittled away as we become progressively desensitised to its value.

The proposed legislation reflects, too, the attitudes of a "well" society to the perceived predicament of people in end-of-life situations where attitudes might well be very different. Great care should be taken not to impose quality-of-life judgements on the sick. A well person may consider the quality of life of an infirm patient intolerable, but as my experience in palliative care has taught me, the infirm patient may have a very different perspective. There is, in fact, no objective way to measure quality of life. Most efforts to do so are based on factors relevant to the physically, intellectually and emotionally well individual. It is easy to overlook the subjective satisfaction of people whose life appears to the "well" person deficient.

I have seen the unreserved love between parents and their children who live with what seem to the able-bodied observer intolerable disability. Likewise in the world of adult palliative care, I have witnessed the loving care of children nursing their adult parents as they become increasingly disabled with progressive disease.

In both instances I have seen precious moments of love and life occur that are unpredictable in their occurrence but, in my opinion, of far greater value than any perceived "loss of dignity". Changes in circumstances, too, may put previous decisions about life issues in a different context. I have witnessed patients who held very firm views on euthanasia become ill and then change their attitude completely and want to live every moment of available life. The benefits of life seem to outweigh what was previously thought to be the "loss of dignity" involved with progression of illness.

The usual non-medical arguments one hears in support of physician-assisted suicide — concern about being a "burden" to loved ones, fear of "loss of dignity" — come across as spurious in the context in which I work.

Many of the patients I deal with, who have had long-term debilitating and life-limiting conditions, could be perceived as having been a "burden" to their families for much or even all their lives. Some have never had the so-called "dignity" of autonomy and have always relied on others in meeting their most basic physical needs.

Should that diminish the value of their lives? Would that justify making a physician legally available to deliberately bring a premature end to those lives, to relieve the perceived "burden" on their families and end the "indignity" of dependence?

As for pain, it is my primary job, as a palliative care physician, to make my patients' lives as free from pain and suffering as humanly possible. And there is much I can do, very effectively, in this regard.

A great deal of the fear healthy people have of pain in end-of-life situations is, in fact, unfounded.

In extremely rare cases, a patient may, with consent, be sedated at the end of life. That option is always there. But even in such cases, the intention is beneficent, the primary motivation being to relieve pain and suffering when no other method is available.

But it seems to me oxymoronic that a doctor be asked to prescribe medication and instruct patients on their use with the express aim of shortening a patient's life.

One final concern I have about the proposed legislation is that its passage may create suspicion about motives and hinder the development of a therapeutic relationship between the doctor and the patient.

The development of trust is very difficult when treating patients with life-limiting illness. Patients' and carers' thoughts could easily become contaminated and confused, and there is the possibility that patients with life-limiting illness may be denied appropriate end-of-life care due to the fear that doctors may be purposefully shortening life.

In short, my fear is that the passage of a bill legalising physician-assisted suicide would confuse and possibly even endanger the practice of palliative medicine, which has an increasingly vital role to play in an ageing society like ours.

Rather than pass legislation, however well-intentioned, that is divisive and open to question, a civilised society would be far better served by promoting and providing adequate palliative medicine, which, to its credit, this current State Government is striving to do.

Dr Adrian Dabscheck is a palliative care consultant at the Royal Children's Hospital and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. These are his personal views and do not necessarily reflect in any way on his places of employment.

Let the sufferers decide their fate

It is tyranny for others to impose their beliefs on those who are ill and wish to die.

THE Medical Assistance (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill had its second reading in the Legislative Council on June 11 and was scheduled for further debate today, although this may be delayed.

If passed by the Victorian Parliament, the bill — sponsored by Ken Smith (Liberal) and Colleen Hartland (Greens) — will allow a doctor to help an adult, competent patient with a terminal or advanced incurable illness who asks for assistance in dying.

At present, the law forbids this type of help and numerous people are forced to continue suffering intolerably — with such relief as palliative care may provide — until death comes. Small wonder some commit suicide, often in horrifying and degrading circumstances.

In a relatively small number of cases, a compassionate doctor is willing to defy the law and provide the help that is sought, but only at the risk of being charged with a criminal offence, and being disciplined or barred from medical practice.

Australia lags well behind other jurisdictions. More than 30 million people in Belgium, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Oregon in the United States now have the right to seek medical assistance in dying.

Periodic opinion surveys show that the great majority of Australians believe patients should have the same right. In the latest survey (2007), support was at 79.7% across Australia, and over 80% in Victoria. Oddly, although the hierarchy of the Catholic Church is the main opponent of reform, more than three in four Catholics appear to be in favour.

The argument against reform is mainly religious: God alone may dispose of human life. But that is irrelevant to the issue facing Parliament. Criminal law does not exist to enforce particular religious beliefs; it exists to prevent harm. That is demanded by the separation of church and state and by our liberal democratic traditions. Consequently, opposition to the proposed reform can be justified only if it can be shown that recognising a person's right to be able to call on a doctor's assistance in dying would cause serious harm to society, a harm that outweighs the right to personal autonomy.

To establish that kind of harm, opponents often talk vaguely and portentously about a lessening of respect for human life. But to recognise the right to seek medical assistance in dying is to affirm respect for the life of the cognisant human being who wishes to exercise that right.

Two further arguments against the bill are based on the risk of some form of specific harm. The first is that corrupt doctors or greedy relatives will use the legislation to disguise decisions made by them rather than the patient or to enable them to put undue pressure upon people to request assistance in dying. That risk exists at the moment. The creation of a closely regulated environment will probably decrease it, by increasing attention on end-of-life treatments and decisions by doctors and patients. It will certainly not add to it.

The second "harm" relied on by opponents to the bill is that it will put pressure on people, particularly those suffering from an advanced incurable illness, to seek assistance in dying when their decision is not free and voluntary. That risk can be met by carefully framing the procedures to be followed before assistance in dying can be provided. The bill does that. Before requesting assistance, the sufferer must be fully informed about the illness and options for its treatment (including palliative care), and at least two (sometimes three) doctors must be sure that the decision to seek assistance is free and voluntary.

A final argument often put against dying-with-dignity legislation is that the reform is unnecessary because of the wider availability of palliative care. That argument is factually wrong. Everyone is pleased by the increasing availability of palliative care. But there are still situations in which it simply cannot be provided. Just as importantly, there are situations in which it does not work successfully.

In the absence of serious harm being caused to others, we are not entitled to impose our own ideas and choices on others. People should be free to choose palliative care if they wish; it should not be imposed on them. That is the fundamental proposition on which the bill is based. The law now denies it.

Almost 20 years ago, in "Cruzan v Director, Missouri Department of Health", Justice Brennan of the United States Supreme Court recognised that respect for individual autonomy demands that the sufferer, not someone else, choose the circumstances and moment of his or her death. This is one of the most important of human rights. More recently, in his book, Life's Dominion, Professor Ronald Dworkin put the same proposition rather more bluntly: "Making someone die in a way that others approve of, but the dying person believes is a horrifying contradiction of his life, is a devastating, odious form of tyranny."

Members of Parliament should take this opportunity to override a law that is so antipathetic to the liberal democratic traditions at the foundation of the Australian legal system.

David St L. Kelly is a former chairman of the Victorian Law Reform Commission.

Who protects the vulnerable now?

ADRIAN Dabscheck (Comment & Debate, 25/6) says that where palliative care fails, "in extremely rare cases, a patient may, with consent, be sedated at the end of life". This is also called "terminal sedation". In terminal sedation, the patient chooses not to suffer. The physician administers the treatment with the patient's consent, knowing this treatment will result in the patient dying sooner than naturally. The suffering is ended once the medication is given and death follows.

This also describes physician-assisted dying. However, in terminal sedation, the patient takes days to die. There are no safeguards whatsoever to protect the patient — no written consent, no second doctor required, no cooling-off period. There is also no annual reporting to the government.

How often does this practice happen, and who is monitoring it? Has the family put pressure on the patient? How often is the practice carried out without the patient's express consent? Is it only done to legally competent patients? How often is the purported intention of the doctor "to relieve suffering" ever interrogated or proven?

Dabscheck states that where terminal sedation is used "the intention is beneficent, the primary motivation being to relieve pain and suffering when no other method is available". This is exactly what physician-assisted dying legislation is about, as a complement to palliative care in the rare cases where palliative care fails. In these cases, both patient and physician should be protected by law.

I admire paliative care workers and support much better funding of this sector as Australians, living longer, face more prolonged dying processes. However, the proposition that if only better funded, palliative care will relieve the indignity and suffering of everyone who is dying, is simply wrong.

The assertion by Adrian Dabscheck that those of us who support euthanasia legislation — and that includes 80% of Australians if a recent poll is right — have lost perspective or are "desensitised" raises the question of his judgement of human nature and sensitivity.

This is an important debate, but I am concerned that personal or religious conviction, rather than an objective insight into the diversity of individuals and death processes in this wide world, may be behind the mistaken idea that palliative care is the be-all and end-all for everyone.

I am constantly amazed by the inability of individuals such as Adrian Dabscheck to comprehend exactly what is proposed by legalised euthanasia. Suggestions that euthanasia will "impose quality of life judgements" are not simply wrong, but misleading and deceptive and have no place in rational discussion of the issue

Whether or not this deception is intentional or simply reflects a lack of understanding I do not know, but it is simply fearmongering and belongs with the "slippery slope" myth. The whole basis of the "right to choose" principle is to place the decision-making process upon us as individuals and to exclude external imposition of any kind. The level of built-in protection is more than enough to outweigh any abuse of the process.

Dr Dabscheck could not deny that palliative care cannot ease the suffering of 100% of patients. What then of the remainder whose pain and suffering cannot be alleviated? Do we simply ignore them? Do we accept their suffering as an "acceptable" statistic?

What is this inhumane obsession with maintaining life at all cost, even when the cost is borne by the sick and dying among us. We owe it to ourselves to demonstrate true humanity and compassion by allowing each person to control his or her destiny. Forcing our own kind to die with pain and suffering is nothing short of mindless cruelty.

How can an individual's right to choose access to legal and safe end-of-life choices translate to us becoming a burden and therefore feeling pressured to depart this world at a time that suits others? The physician-assisted dying bill is about individual choice and I want my choice. I do not fear a good death, but I do fear not being able to have a good death

Anne Lakh, NorthcoteIn human life, 'value' is a relative concept

MY HUSBAND is terminally ill with motor neurone disease and his body is slowly wasting away. He has decided that he doesn't want to wait until he has lost control over his own life and live in a vegetative state. He would rather end his life when he and only he feels life has become unbearable and not worth living any more. He was lucky that with the support of Dying With Dignity Victoria, and Rodney Syme in particular, this wish has become possible when he decides the time is right.

Although I have a lot of respect for the wonderful work of Adrian Dabscheck (Comment & Debate, 15/6) in providing quality palliative care, I feel that somehow he got hold of the wrong end of the stick when he talks about the fact that physician-assisted dying or euthanasia "reflects a disturbing degradation of the value we as a society place on human life". It is because of lack of this value of human life for terminally ill people that physician-assisted dying is a welcome choice for those who cannot face the pain and suffering in their lives any more. It is the patient's wish to end their life because life is not worth living any more; it has lost its value.

David Kelly (Comment & Debate, 25/6) starts his article with the following phrase: "It is tyranny for others to impose their beliefs on those who are ill and wish to die." And that is exactly right. Everybody should be able to make that choice whether to end their life or not in the case of a terminal illness. We hope and pray that the physician-assisted dying bill will be accepted so that those who choose to end their suffering will be able to have the choice to die with dignity.

DAVID Kelly (Comment & Debate, 25/6) is naive in suggesting that the opposition to physician-assisted dying is mainly religious. Every citizen in our community should feel threatened if there are medical practitioners licensed to kill. The grounds are primarily social, as well as religious. Remember John Donne: no man is an island.

Nor is it reassuring to cite the longstanding practice, particularly in the Netherlands, where the slide from voluntary to non-voluntary euthanasia is well documented. Third, the oft-cited statistic that almost 80% of the community approve of physician-assisted dying in some circumstances should be put alongside the parallel statistic that approximately the same percentage approve capital punishment in some circumstances. Both should continue to be resisted for the same reasons: they are both killing and we make mistakes. Finally, terminal sedation and administering a lethal injection are quite different: one is killing, the other isn't.

THE Age has done well by its readers in presenting opposing arguments on the merits of the assisted-dying legislation (Comment & Debate, 25/6). From a surgical background, but having worked here and overseas in hospices and more recently in palliative care postgraduate study and clinics, I see the issues as clear-cut. Modern palliative in-patient and out-patient care is wonderful and improves year by year. Yet there are a very small number of dying patients whose pain and other symptoms cannot be well controlled; whose days and nights are extended misery, who ask about and plead for assisted dying.

Staff must make kindly blanket statements that such requests are illegal, and the patient/family may be referred to a chaplain or psychologist. Euthanasia has been a taboo topic in palliative care circles. Senior clinicians who are privately sympathetic fear speaking publicly. The opposition logic is well-meant, deeply entrenched, but seems morally and theologically based rather than medically so. We should not continue to ask patients to bear the brunt of our moral uncertainty.

THE proposed physician-assisted dying legislation is being misunderstood and attacked by people who have not informed themselves. They are the same who write the most arrant nonsense about the situation in the Netherlands. Please inquire, find out and reflect before judging.

Newsreader Tracey Spicer has revealed that she came within moments of suffocating her mother, an admission likely to further ignite the debate over whether euthanasia should be made legal.

Spicer's mother, Marcia, died of cancer hours after her daughter could not go through with the act.

"At 3.17am on October 25, 1999, I considered suffocating my mother with a pillow. I didn't view it as murder. It would be an act of mercy," Spicer wrote in an opinion piece in The Daily Telegraph.

She said her parents were "vocal supporters" of the right to die with dignity, and detailed Marcia Spicer's long, determined battle with the cancer that first appeared in her pancreas.

And as her mother's pain became excruciating - "Fleeting moments of consciousness were punctuated by howls of pain" - she felt she had to do something to ease the pain.

"It soon became an obsession. Palliative care nurses were tackled in the corridor and asked whether they would assist in a murder," Spicer wrote.

Spicer said she had purchased a book called To Die Like A Dog, about a woman's mother dying of cancer. The woman had tried to suffocate her mother with a pillow and was later convicted of attempted murder.

While reading the book at her mother's bedside, Spicer said she had decided to take action.

"There was dark silence in the corridor. I picked up a pillow from the floor and walked over to the bed. Even at death's door, Mum looked a picture of health. Her calm visage disguising the decay within.

"I knew it was the right thing to do. But as I looked down at the woman who gave me life, I knew that I could not take hers."

Instead she collapsed on the floor and "sobbed like a baby".

"It is the ultimate paradox to want to kill the one you love the most," she said, adding that thousands of Australians faced this dilemma every day.

"In the heat of the debate about euthanasia, let's take the time to think about these people and their stories, in life's irretrievably frayed patchwork."

Leading the way

NEWS of a dying with dignity bill is fantastic. At last Victoria has some gutsy politicians prepared to do what they are paid for: identify issues troubling our society and develop responses.

For too long we have been aware that, even in our modern, affluent country, with advanced medical and palliative care, there are people who face a lingering, miserable, undignified death. We all hope that no one close to us scores that cruel lottery.

While most politicians will acknowledge that to be so, they much prefer that the issue is not raised for fear the religious lobby will target their electoral standing. A common ploy is to wring ones hands and say "no one has the answer, it's too hard".

There are answers, of course, and they have been proved safe and effective for more than a decade in Oregon.

A time will come when historians will look back on this era and consider it barbaric that we demand that, by inaction, dying humans endure misery we will not allow a domestic pet to endure. Hopefully, Victoria is about to lead Australia into a new enlightened, compassionate era when it comes to dying with dignity.

Not good for me

EUTHANASIA is supported by an overwhelming vote of between 75% and 85% in every poll, yet it has yet to be made legal, due largely to the influence of the churches.

At least one religion says pain and suffering is good for you. It may be good for them, but it sure as hell is not good for me.

Certain topics are considered taboo in Australian society, topics such as rape, child sexual abuse, child pornography, SEX AND SEXUALITY, abortion and other related topics. One of the taboo issues of the moment is of course euthanasia, as a recent attempt at changes to the law in Victoria proved.

On 11 June 2008 the Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008 was introduced in the Victorian parliament by a member of the Greens party. Before there was the possibility of proper debate in the community at large and in the parliament in particular, the Bill failed to pass the Legislative Council and was defeated on 10 September 2008.

This is a topic which federal, state and some Territory politicians are doing their best to sweep under the carpet, as a consequence of which the current federal government, as well as the previous one are trying to censor the subject from being discussed in any medium at all, including, of course, the world wide web.

Between 1983 and 1997 many hundreds of people in Australia and around the world died agonising deaths from AIDS-related diseases, and of course in many countries this is still occurring on a daily basis. In Australia many people took the option of dying with dignity by euthanasia methods, self-administered or assisted. While I was studying for a Master of Health Sciences (HIV Studies) post-graduate degree between 1983 and 1995 I came across many articles in journals and newspapers which referred to the AIDS crisis and incidents of euthanasia.

I intend to put on this web page in chronological order many of the articles and essays I discovered during the course of my studies.

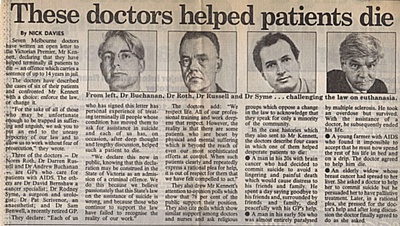

Article in the Sydney Morning Herald as the gathering storm starts to rage!:

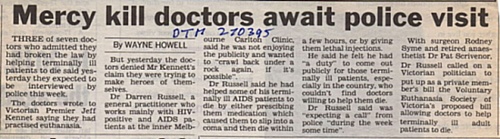

Article in Daily Telegraph Mirror:

Letters to the Editor - Sydney Morning Herald:

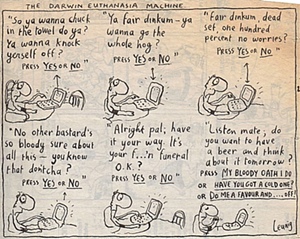

Michael Leunig gives his ideas on euthanasia in The Age:

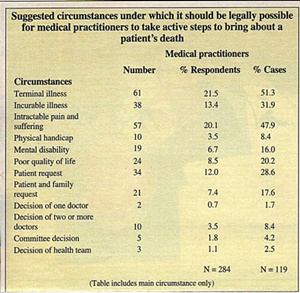

Article in Medical Observer:

Article in Australian Doctor:

Michael Leunig is still thinking about euthanasia in the Sydney Morning Herald:

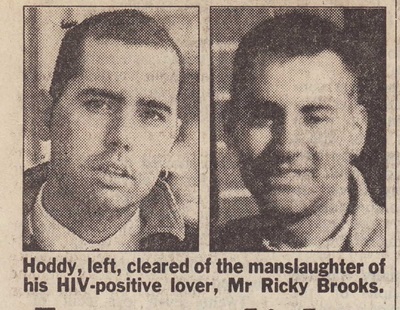

A male nurse who helped his HIV-positive lover attempt suicide was cleared of manslaughter yesterday after a magistrate found there were three possible causes for the man’s eventual death.

The ruling was immediately welcomed by the AIDS Council of NSW, which revealed yesterday that mercy killings of people with HIV were attempted in Sydney about four times a month.

About half of the attempts were “botched”, according to the council’s executive director, Mr Don Baxter.

“Naturally, that’s a really traumatic experience for the family and friends and lovers and, of course, for the person themselves,” he said.

“This is the only case we know that has come to court, but in some cases the traumathat’s caused by the means of death is actually worse. In this case Mr [Leslie] Hoddy, as a trained nurse, was actually able to assist in a way which didn’t lead to as traumatic [circumstances] as some other experiences that we’ve heard about.”

Hoddy, 30, had pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting the suicide of his lover of four months, Mr Ricky Brooks, in a Darlinghurst hotel room on October 7 last year. Hoddy was also charged with the more serious offence of manslaughter but had not entered a plea.

The Downing Centre Local Court had been told that Mr Brooks had telephoned Hoddy to come to the hotel to help him “do it properly.”

Hoddy obliged by crushing 15 tablets of codeine phosphate into a glass of orange juice for him – as requested – but left Mr Brooks, who was still alive, after 10 minutes. Mr Brooks was found dead later that day.

A post-mortem examination later revealed he died after ingesting lethal doses of the narcotic codeine and the anti-depressant drug dothiepin.

In dismissing the manslaughter charge yesterday, the magistrate, Ms Gillian McDonald, said it was not disputed that Hoddy had committed a dangerous and unlawful act. But whether that caused Mr Brook’s death was questionable.

She said it appeared from the evidence that Mr Brooks, who had been in the hotel room “for some hours” before Hoddy arrived, had ingested the drug dothiepin, and may have also taken some codeine tablets.

Citing expert evidence given by a forensic pathologist and pharmacologist, who were unable to say which of the drugs induced the death, Ms McDonald said: “So much of this case is difficult because we have really little definitive evidence as to the actions of Mr Brooks prior to his death. But, to my mind, the prosecution cannot establish that it was the defendant’s actions that did in fact cause the death.”

Ms McDonald found there were three possible causes of death – codeine poisoning, dothiepin poisoning or a combination of both. She said one [dothiepin poisoning] was “not in any way related” to Hoddy’s actions which must constitute a “reasonable doubt about Mr Hoddy’s liability”.

Mr Baxter also revealed yesterday that the AIDS Council of NSW was “often in the invidious position” of being asked for advice on how people might carry out euthanasia. Asked if doctors had been involved in the reported mercy killings, he replied: “a range of people assist with active euthanasia at the moment, yes.

“We are in a situation where, if we’d had legal euthanasia reform, then Mr Hoddy would not have been put through all of this and Mr Brooks would have been able to discuss openly with his doctors, his friends and family, what he intended to do. He may even have chosen not to do it.”

Hoddy will be sentenced in the Sydney District Court on a date to be fixed.

*******************************************This is an actual case, abbreviated from HIV/AIDS Legal Link, Vol 7, No 1, March 1996. Used at suggestion and with permission of the AIDS Council of NSW.

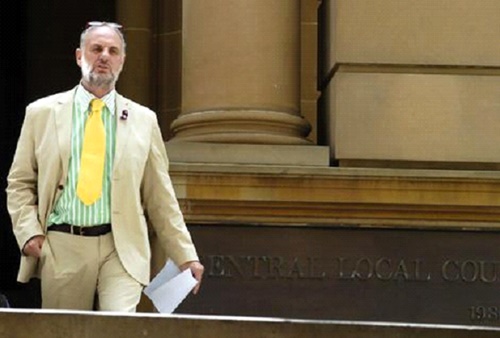

The article was written by David BuchananA man who helped his lover with HIV to die has been acquitted of manslaughter.

He received a good behaviour bond for aiding and abetting an attempted suicide.

Leslie Hoddy, 30, was charged with manslaughter, and aiding and abetting suicide, after he contacted police and told them he had helped his lover to suicide using prescription medications.

The body of Ricky Brooks was found in a Sydney hotel room on 7 October 1994.

Subsequently Mr Hoddy told police that he and Mr Brooks had been hospitalised with HIV related conditions a number of times and had previously attempted suicide. Mr Brooks' doctor told the court which sentenced Mr Hoddy that Ricky Brooks had been quite unwell, and that the combination of his illnesses, disabilities and his medications would have left him very unhappy. Mr Brooks had been diagnosed HIV positive in the early 1980s.

Tablets to help lover dieMr Hoddy said his lover had telephoned him saying he had messed up his attempt to kill himself. He asked his boyfriend to help him "do it properly". Mr Hoddy, an enrolled nurse, went to the hotel room where he and Mr Brooks talked about their lives and hugged and cried together before Mr Hoddy crushed 15 codeine phosphate tablets for Ricky to take with juice.

When Mr Hoddy left, his lover was still alive although slurring his speech and slumped on the bed. Police later found two suicide notes in the room, one of them to Mr Hoddy.

UnitingCare NSW.ACTA magistrate discharged Mr Hoddy on the charge of manslaughter on the basis of the toxicology evidence and Mr Brooks' medical history. The latter showed Mr Brooks was habituated to morphine derivatives and thus the level of codeine phosphate found on post - mortem would not in Mr Brooks' case have necessarily been fatal. The drugs found on post - mortem included lethal levels of at least one other drug, plus a number of other drugs.

Further, based on Mr Hoddy's statement to police, Mr Brooks had already consumed codeine phosphate before Mr Hoddy arrived.

Accordingly, the magistrate found that it was not possible to say that the drug administered by Mr Hoddy had caused Mr Brooks' death. For this reason, the prosecution then changed the second charge to one of aiding and abetting attempted suicide. To this charge, Mr Hoddy pleaded guilty and he was committed for sentence.

SentenceAt Sydney District Court on 28 November 1995, Judge Solomon heard testimony by Mr Brooks' and Mr Hoddy's doctors. Mr Hoddy is a "long term survivor" of HIV. As well as psychiatric and psychological evidence as to the effects of the case on Mr Hoddy, the judge received evidence from the Director of the AIDS Council of NSW,and Ankali, an HIV/AIDS support group, about the increased hardship suffered by people with HIV if they are imprisoned.

Mr Hoddy's barrister told the court that HIV related suicides were not uncommon and that a heavy sentence would not deter AIDS suicides, rather it would only affect the reporting of suicides to police.

Judge Solomon imposed a three year good behaviour bond on Mr Hoddy. He took into account the "tragic circumstances" of the case and the ill health of Mr Hoddy. The judge said that Mr Hoddy was not motivated by anything but his affection for Mr Brooks, who had terminal AIDS and "was in great physical and psychological distress".

The court accepted that Ricky Brooks chose to end his life, by suicide, and then by assisted suicide.

Assisted suicide is illegal, and one reason for euthanasia legislation is to make assisted suicide in such cases legal, so people like Leslie Hoddy do not have to go to court for helping someone die at their own request.

What do you think you would have done if you had been in Leslie Hoddy's place?The court accepted that this was a case of assisted suicide.

AIDS sufferers say that many of them will continue to choose to die by suicide, rather than wait for AIDS to run its full course. On the other hand many AIDS sufferers do not suicide, and wait for the disease, or some complication, to end their lives.

How should society deal with such situations?Euthanasia legislation would provide a process for requesting help with dying, so that there were at least some safeguards for all involved.

What would be the advantages and disadvantages of such legislation (if carefully formulated with adequate accountability mechanisms - compared to the present situation?

Michael Leunig makes his contribution to the Darwin Euthanasia Debate - in the Sydney Morning Herald:

Morris Gleitzman writes an open letter to Kevin Andrews about his Euthanasia Bill in Federal Parliament - in the Good Weekend:

This article appeared in The Age newspaper on 25 March 2009:

Angie Belecciu, just days before her death: "We humans are not humane to our own species." Photo: John Woudstra

WHILE most of us were preparing our evening meals on Monday, Angie Belecciu was checking into a motel room on the Mornington Peninsula with a recipe to die.

After an 18-year battle with cancer, the former palliative care nurse was determined to end her life with dignity. She did not want to be alone. Nor did she want to be lying in an unfamiliar bed where a stranger would find her.

But as she told The Age last week, laws banning euthanasia and assisted suicide in Australia had forced her to devise a secret plan to achieve a painless death - and to hide many of the details from those she loved most.

Angie's wish: death with dignity

After nearly two decades fighting cancer - and days before she took her own life - Angie Belecciu says Australia needs to rethink its euthanasia laws.

The mother of two, whose body was riddled with bone cancer, said her illness had left her with two choices: letting her body deteriorate until she was slowly euthanased in a hospital bed with family and friends around her - or dying a swift, peaceful death without them. After months of meticulous planning, Ms Belecciu, 57, carefully executed the second of the two on Monday. She was found yesterday morning in her favourite, softest pyjamas. It is unclear if she had been alone or not.

Ms Belecciu contacted The Age last week with the help of Exit International, a pro-euthanasia group she had sought out during her illness, to tell her story. After explaining the constant pain that had gripped her bones in recent months, she said she wanted to create debate about legislative change.

"We humans are not humane to our own species. If I was an animal, it would be cruel and against the law to allow me to continue my life," she said.

"If I had one wish it would be that one day, everyone will have the right to choose," she said. "It doesn't mean you have to take that choice, but you should have it."

In a letter to the founder of Exit International, Dr Philip Nitschke, Ms Belecciu said she felt blessed to have the means to achieve her goal, but resented being made to feel like a criminal to pursue it. "Our laws at present say (that) even though I have been able to think, reason and make choices all my life, I am not able to know when I've had enough."

Fearful of the long, arduous deaths she had watched in palliative care units, Ms Belecciu arranged last year with another terminally ill man, Don Flounders, to obtain Nembutal - a potent barbiturate commonly used to euthanase animals.

Restricted by her illness, she paid for some of the costs Mr Flounders and his wife Iris faced to travel to Mexico, where the drug could be purchased over the counter at veterinary clinics. When Mr Flounders arrived with her Nembutal last year, Ms Belecciu said she had never felt more relief: "The weight was gone, my fear was gone."

But after Mr Flounders made his journey public by talking to Channel Seven, his and Ms Belecciu's homes were raided by federal police last year. The police did not find their drugs and the case appeared to be closed.

On hearing of Ms Belecciu's death this week, Mr Flounders said he would not be surprised if he and his wife's "file" was reopened. "What are they going to do? Put us in prison? I'm bed-ridden most of the time, so it would have to be in hospital, which would make it even worse from a publicity point of view for them," he said.

Dr Nitschke said although he might also be sailing close to the edge of the law for his organisation's role in introducing Mr Flounders to Ms Belecciu, he did not think the police would arrest Mr Flounders, who has mesothelioma.